- Home

- Stephanie Perkins

The Woods Are Always Watching Page 11

The Woods Are Always Watching Read online

Page 11

Best she could tell, the sunglasses weren’t there. Maybe they had dropped out during the shuffle in the storm.

Her hand dropped and clenched, digging into the branches and mud. Josie screamed. Wept. Tore at the earth until, unexpectedly, she grasped the small object that had fallen from her pack. Recognizing it, she yanked it free and drew it to her lips.

The sound pierced the woods. Birds scattered from the treetops.

Josie squeezed the emergency whistle so tightly that the orange plastic bit into her fingers. She whistled without knowing or caring who she was trying to call.

NEENA

NEENA WAS HALFWAY back to the Wade Harte Trail before realizing that she’d forgotten her inhaler. The journey had been so much lighter without her pack. She’d run. She’d flown.

And then she’d jogged.

“Jogged” was a bullshit way of saying that she was running slowly because she didn’t have the strength to run fully. Her adrenaline had vanished at the first indication of tightness prickling her chest, but that prickle was merely a caution. Not even a warning. She stopped before the coughing could begin, checked in with her lungs, and sipped her water. Her asthma wasn’t mild, but she dutifully puffed her steroid inhaler every morning and night, so the medicine was already built up in her system. And she’d used the rescue inhaler—the fast-acting, emergency inhaler—this morning, too. She would be fine.

She would have felt better if she had remembered to grab the rescue inhaler, but there had been the foot. Josie’s mangled foot. The foot had been distracting.

An estimated six or seven miles stretched between her and the car. Returning for the inhaler would mean an additional hour of jogging—the last thing she wanted—so Neena continued to retrace their prints through the mud. With her sharpened gaze, she felt like a hunter stalking its prey, except . . . by following her own tracks, didn’t that mean she was also the prey?

The path grew difficult to make out once Neena reached the pre-storm tracks. The footfalls weren’t as deeply imprinted, and many had washed away. Supplementing with the bottle caps, which took longer to find, her progress further slowed.

She would be fine. Josie would be fine.

They’d both be fine, and everything was fine.

The rainfall evaporated, but her clothing remained soaked with sweat. She yearned for dryness. Fluffy bath towels and ionic hair dryers. Would she have to run back with the emergency responders, or would they fly out in a helicopter? Shea butter lotion and freshly laundered pajamas. Did you have to actually be missing—or near dead—to get a helicopter? A mattressed bed and cool summer linens. What level of emergency was a teenage girl with a broken foot stuck inside of a hole?

But it wasn’t just a broken foot. The graphic injury was most likely a compound ankle dislocation. Again and again, Neena rehearsed the plan in her mind: Get to the car and call 911. Then, call her parents. Then, Josie’s mom. A mixture of premature anxiety and humiliation surged through Neena. Their parents would be frantic, but, even worse, they would be disappointed. She and Josie had failed their first test at being self-reliant adults.

As the bottle-cap trail left the forest floor and headed steeply upward to meet the ridgeline, Neena cursed herself and Josie for deciding to leave the main trail in the first place. She hadn’t even reached it yet. The mileage technically hadn’t even started.

An unknown noise pierced the forest chatter.

The fine hairs on her neck stood alert. Quiet rippled out as every woodland creature strained to place the sound. It seemed far in the distance, though she couldn’t tell in which direction. But the noise was human-made, and it was insistent.

The answer crashed into her like an avalanche. The whistle.

Had Josie’s condition worsened? Was she asking for Neena to return, or was she calling out for help from somebody else? Why hadn’t they thought to teach themselves any whistle signals or codes?

Neena booked it toward Josie. Seconds later, she stomped back toward the ridgeline. The whistling stopped. She spun around again. A growl of frustration escaped, snowballing into a yell, and she screamed Josie’s name.

Her heart floundered. The scream was futile. Josie wasn’t close enough to hear it, and Neena wasn’t close enough to turn around. But what if Josie’s condition had worsened, and she needed immediate assistance? Or, what if another hiker had found her, and they were signaling for Neena to return? Then again, what if Neena did return, but then found Josie in the exact same condition? Or, what if her condition had worsened, but Neena still couldn’t help? Either way, Neena would only be prolonging the agony.

Even though it felt deeply wrong to ignore Josie’s cries for help, Neena chose to jog away.

JOSIE

WAS IT UNSAFE to fall asleep, or was that only for concussions? With a shot of disoriented panic, Josie touched her forehead, expecting blood.

Her head was fine.

She settled back against her pack. Everything hurt, though it was tolerable if she didn’t move. The hole was muggy, and her eyelids were heavy. Mud caked on her skin in reptilian flakes. Hazily, she flicked off the scales. Here, there. Wherever the crust peeled up. Her body smelled of the warm woods—of dank verdure, crumbling soil, and rotting vegetation. How fitting if the sinkhole collapsed and the earth swallowed her whole.

After her father died, nature overtook their house. Yellow pollen floated in through the window screens and nestled into the cracks of the furniture. Dust thickened and transformed into grime. Greasy dishes crusted in tottering stacks, and abandoned saucepans molded with woolly spores. Rodents appeared, drawn by the glazy smears and scattered crumbs, and shit their droppings along the baseboards and into the open drawers. Photographs faded on the fridge and weren’t replaced. Appliances broke and weren’t fixed. Tree limbs fell and weren’t hauled away. Weeds decimated the flower beds and annihilated the unmown lawn. Josie and Win taught themselves how to do laundry, but even their clean clothes were heaped in piles like discarded corpses.

When Josie became friends with Neena, she tried to block her from knowing or seeing, but Mr. and Dr. Chandrasekhar had insisted on meeting her mother. Shortly after, their house had magically opened to Josie after school. She was absorbed into their afternoon and evening routines. She did homework and ate meals at their table, watched TV and played Xbox on their sofa. The space was safe and sacred, and even after the counters in her own home were eventually scrubbed and sterilized, it remained her safe space.

Only yesterday, she’d wondered if nature might become her new haven. She had imagined spending months out here, trekking all two thousand miles of the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine. Now, she’d either never leave or never return.

Had Neena reached the Wade Harte yet? Josie dreamed of it like a GPS map from above, following the moving dot along the ridgeline.

Go, she urged the dot. Run, run.

NEENA

NEENA BENT OVER in a coughing fit. Her chest was taut. The ridgeline was just ahead, but she couldn’t continue to climb until her breathing had calmed. Steadying herself against a stalwart birch, she sipped more water. It was unrefreshingly warm and tasted like the woods. If only she had one of those ridiculous-looking pouches with the tube straws that people carried on their backs. Her arms were already sore from taking turns holding the bottle.

Spongy mushrooms with ribbed gills scaled the birch’s trunk. Did the mushrooms harm the tree as they fed? It seemed sinister how fungus concealed itself—just out of sight—before erupting from the earth overnight, everything suddenly covered in mold and decay. Did it grow as quickly as it appeared? Or did it fester below the surface for weeks, months, even years before being pushed to its breaching point?

Josie was always future tripping; Neena had never known anybody more afraid of things going wrong. But maybe if they’d been friends before her father’s accident, Josie would have been a different person. This

idea made Neena uneasy, too. Would she have still fit into Josie’s life if her father’s absence hadn’t carved out a void?

Somehow, the sinkhole felt to Neena like it was her fault. Like she had willed the danger into existence by denying its possibility. By not listening to Josie. Neena had said awful things, unforgivable things, but Josie had said true things. Neena was selfish.

When her parents had immigrated from Kolkata to Charlotte, her mother had to do her residency all over again. Her father had to pass the local bar. Later, when Neena was in elementary school, her mother had accepted a prestigious job at Mission Hospital, and they had moved to Asheville. Every day, her parents woke up at four a.m.—Ma to cook their meals, and Baba to commute the two hours back to his job in Charlotte. Ma would drive Neena and Darshan to school and then drive herself to work. Baba would drive home in time to pick them up from school. Yet they never complained. Neena had never heard them grouse about being too tired or stressed or busy.

They had sacrificed their own comfort to give their children access to greater opportunities. Every choice they made was for the people they loved, never for themselves. Darshan had followed in their mother’s footsteps and was currently premed. Neena had rebelled and chosen a path that served herself. Not only was she turning her back on her parents’ wishes, she was also abandoning her best friend—the one person who completely understood her and was always by her side.

Even now, leaving to get help . . . Neena was still leaving. Should she have tried harder to get Josie out of the hole? Her instinct had been to go and to go fast. It was the right decision, but it was also an uncomfortably close parallel to what was about to happen. Because even if Josie did find something or someone that she loved in college, she would still have to take care of her mother. By being healthy and successful, Neena’s parents had given her the freedom to leave. Guilt chewed Neena up. She felt the dull, hot press of her phone in her pocket and wished she could text her ma.

Stop wasting time, Ma would text back. This situation is not about you.

Neena’s selfishness burned everything it touched.

She pushed away from the birch and, a few minutes later, finally reached the Wade Harte. The daunting miles spread out, before her and behind her.

JOSIE

THE MOLD WAS spreading. Josie noticed it first in the bottom corner of a wall, an indistinct greenish-black spot, and scrubbed it away with a scouring pad. The wall dried, and the spot reemerged. As she scrubbed again, her eyes caught on another area, about the size of a quarter. She scrubbed this, too, before discovering even more. The spores grew fast, impossibly fast, like spilled ink or soured milk. She stumbled backward as they swallowed the wall and then shot off across the mopped floors and sterilized surfaces.

Chaos reclaimed her house in splatters of grimy, fungal watercolors. Josie glanced down at the yellow scouring pad in her hand, now blackened and rank, and discovered the darkness wriggling up onto her fingers. She dropped the pad, but the stain was already smothering her wrists, overtaking her arms. She ran to the sink, but the faucet was dry. She ran to the door, but the knob wouldn’t turn. She ran to the windows, but the sashes were sealed shut. The mold crawled over her skin, alive and devouring—

Josie woke with a racing heart. An insect horde was swarming inside the sinkhole. Mosquitos, gnats, and flies vied for her immobilized body, attacking her exposed skin. Their host cried out. Flapping and waving her arms, she forced them off, but they careened straight back. Josie swatted them against her bitten flesh. She fumbled for the bug spray and bombed them. Her tormenters hurtled away.

Alone in the poisonous mist, she coughed and gagged. She leaned her head back to try and gulp at the fresh air, but it was too high to reach. Though the clouds had moved along, the wan color of the late-afternoon sky had barely changed. It was impossible to tell how long she’d been asleep. Her body spasmed. The buzzing wings haunted.

Slowly, then rapidly, her sunburn reintroduced itself. Her skin was angry pink and screaming hot, inflamed in the areas where she’d flicked off the dried mud. If only she’d remained covered in it like an adorable baby elephant. If only she’d remembered to reapply sunscreen at lunch. If only she hadn’t fallen into this hole.

If only they’d never gone on this trip.

Her mind retraced the minutes before her fall. Getting lost, fighting. What were the chances of both bottle caps falling off the tree, anyway? What kind of rotten luck was that? Unless it hadn’t been luck at all. She considered the rubbed-away bark on the other tree. The handwritten log of bear sightings scrawled across the plywood notice board at the trailhead.

She spun the stone ring around her finger in her usual nervous habit. It moved with resistance, tight from the heat. Less than a week after they’d bought the rings, she’d dropped hers into a cast-iron sink. It had shattered on impact. She’d had to borrow money from Win to replace it but had never told Neena, because she didn’t want her to believe that this new ring meant anything less. Josie was careful with it now, always touching its smooth finish to ensure that it was safe.

She thought she’d been safe with Sarah. They’d been best friends since the first grade. But less than a year after Josie’s father died, Sarah had inexplicably abandoned her for a group of girls who had boyfriends and vaped scented clouds of cotton candy in the school bathrooms. Was it because Josie wasn’t fun anymore? Because she worried too much? Because she was depressed? Maybe she put too much pressure on her friends to keep her happy. Maybe that’s why they always left—the job was too big.

The bandaged mass on the other side of the hole was crusted red, but Josie’s thoughts remained as detached from her ankle as it was from her. Her skin burned. Her bites itched. She fantasized about bathing, naked and clean, in a pool filled with clear aloe vera. The cold gel would hold her body aloft like gelatin. Protect her like a cocoon.

I could wait like that.

She placed herself inside the cocoon.

I can wait like this.

Something rustled in the woods. Her eyes popped back open.

“Neena?” Gently, she twisted, looking upward through her crooked frames. Her head throbbed with muzzy euphoria. She called out louder, “Neena?”

The rustling stopped.

No. It was impossible for Neena to have returned before dark. Unless she’d found help along the way?

“Neena? Is that you?”

Long seconds passed, and the noises resumed. As the shrubs shifted and resettled, her thoughts again sprang to bears. Her stomach plunged. The sounds grew close enough to become distinct—and then sharpened into footsteps. With unshakeable certainty, Josie knew the gait was human. And she knew Neena would have called back.

“Hello? Can you hear me?”

The footsteps continued toward her. Heavily, steadily.

“Help! Please help me.” Her cries turned hysterical. “I’m in a hole! I’m down here!”

The footsteps stopped—just out of view. She was sobbing again, begging for a response. Something weighty and substantial was lowered onto the ground above her.

And then a man peered over the edge.

NEENA

THE JOGGING HAD ceased. Neena was speed-walking now, her formidable boots clomping low dust clouds along the balds. The hottest hours of the day were over, but the sun still persisted in the sky. She hoped to reach Deep Fork before dusk and to be down as much of Frazier Mountain as possible before nightfall.

Before this trip, Neena had never imagined that her upcoming separation with Josie would be anything more than locational. Their friendship was too strong. It could survive anything. Now, she wondered if she had been lying to herself the whole time.

She already knew she had been lying to Josie.

Freshman year, Neena’s then best friend had joined the cross-country team. Physically unable to participate, when Neena had seen Grace running around the track with her new

teammates—matching cardinal-red tank tops, ponytails bouncing behind them—she had felt targeted. Spurned. It felt like she’d been rejected for an entire girl gang. But the awful truth was that Grace had never rejected Neena.

Neena had rejected Grace.

Cutting the ties first became Neena’s way of winning. Except the cold shoulder and ignored texts had only left Grace hurt and confused. Remorse had overwhelmed Neena, but, instead of apologizing, she averted her gaze. Instead of apologizing, she clung to cowardice.

Later, when Josie inferred that Grace had instigated the dumping, Neena had never corrected her. Partly because she felt sorry for Josie, but mostly because she still felt ashamed for how she had treated Grace.

It was shocking how quickly angry words—just like silence—could alter a shared history into insignificance. Neena knew Josie’s order at Waffle House (patty melt with extra pickles, hash browns covered and capped). Where she kept her favorite lip gloss (Burt’s Bees in Sunny Day, the back pocket inside her purse). How she couldn’t roll her tongue (and rolled it using her fingers as a joke). Who her first crush was (Hiccup from How to Train Your Dragon). Neena was an encyclopedia of Josie knowledge, and now that book threatened to become as useless as the volume on Grace.

The surrounding panorama was lonely and foreboding. The sunlight was interrogational and oppressive. The clamor of insects shook the air like the tail end of a rattlesnake. Neena stumbled and gasped, overcome. It felt like someone was squeezing away her breath.

JOSIE

THE MAN WAS white. He wore a ball cap low over his eyes, and his body was broad and thickset. His beard was thick, too. He appeared to be somewhere in his thirties, maybe, and, though it was difficult for her to see his expression clearly, the energy behind his stare was intense. It sucked up all the air. He didn’t speak.

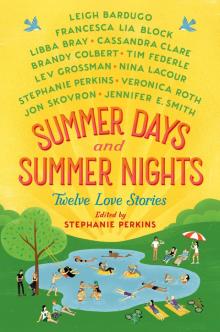

Summer Days and Summer Nights: Twelve Love Stories

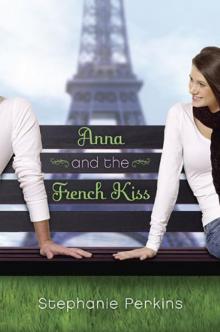

Summer Days and Summer Nights: Twelve Love Stories Anna and the French Kiss

Anna and the French Kiss Lola and the Boy Next Door

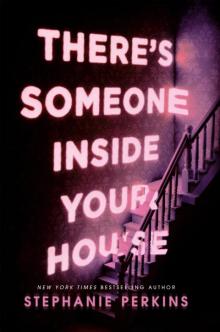

Lola and the Boy Next Door There's Someone Inside Your House

There's Someone Inside Your House Isla and the Happily Ever After

Isla and the Happily Ever After The Woods Are Always Watching

The Woods Are Always Watching Summer Days and Summer Nights

Summer Days and Summer Nights